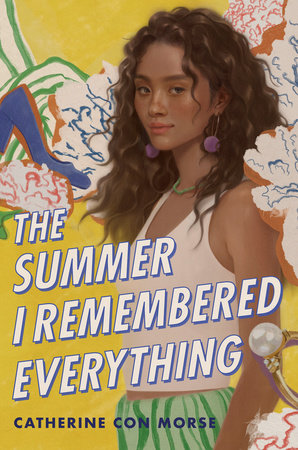

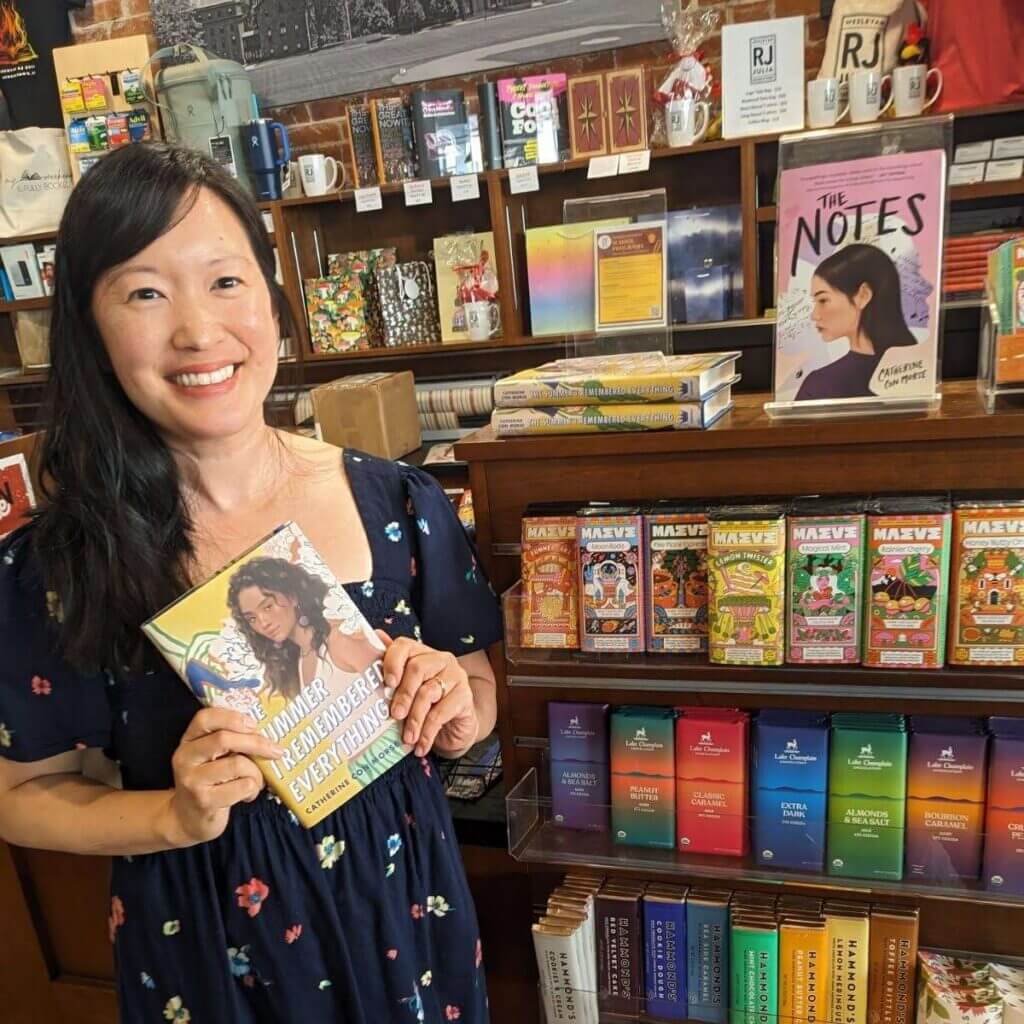

What if you and your mom shared the same name? And what if you both were writers with dreams of publishing your stories? Well, Catherine Con Morse, author of The Summer I Remembered Everything, doesn’t have to wonder “what if?”—she’s lived it! Read on to hear about her experience sharing a name and a passion for writing with her mother.

My Mom Stole My Pen Name

by Catherine Con Morse

It’s 2004, I’m a junior in high school, and my family and I are at a holiday party in our neighborhood.

“I’m Catherine,” my mom says when she introduces herself.

“Hi, I’m also Catherine,” I say, trying to make a joke out of it before the other person does—or worse, gets confused. Because I want to be different from Mom, I say it with a huge smile on my face, eager to appear friendly to contrast her stoic elegance.

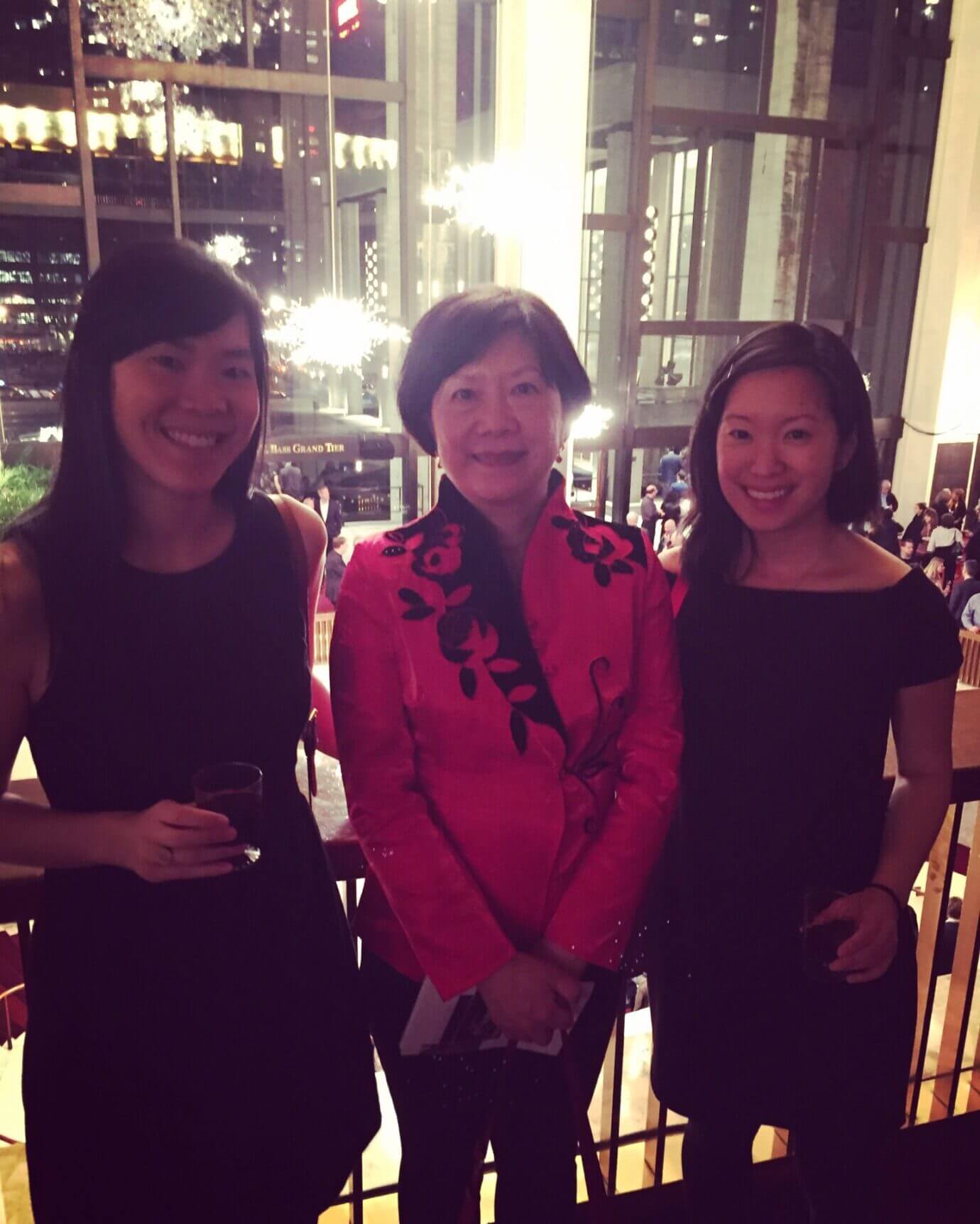

Catherine Con: It was a satisfying name to say aloud, it looked great printed, and I loved signing it with big swooping C’s. But by the time I was in high school, I hated that my mom and I shared the same name. We were one of the few Asian families in our neighborhood. Did we really need to have this other thing that made us weird? It irked me that I was trying to be my own person, to figure out who I even was, and yet I could never escape my mom’s name.

—

Fast-forward to the spring of 2020. My parents told us over Zoom that they had decided to sell the house where my sister and I had grown up. I surprised myself by getting teary about it, and my cool younger sister made fun of me for crying, as Emily does to her annoyingly perfect older sister, Tessa, in The Summer I Remembered Everything. (For the record, I was never as annoying as Tessa.) Stuck at home with newfound free time, I began drafting Summer. But I didn’t mean to start writing a book—I just wanted to capture what it was like to grow up in the South Carolina suburbs with my Taiwanese mother and Chinese Costa Rican father (as Emily says, we were just your typical tri-country family). As a teen, I spent long summer days reluctantly swimming on the neighborhood team and trying my best to get out from under my mother’s thumb.

Like Emily’s mom, my mom could be pretty direct. She was forever telling me to go blow-dry my hair, or (this was especially Southern) go “put some color on.” Once, she told me that if I didn’t start talking more, people wouldn’t like me. (I’m pretty sure she regretted that later.)

Mom didn’t mince words, even when she was diagnosed with ovarian cancer a few years ago. I found myself feeling sympathetic and annoyed, fearful and frustrated, sometimes in the same hour. Also like Emily’s mom, mine was a tough lady who didn’t take any bullshit from anyone (pardon my language, but that is how Mom talked!) and had some sneaky ways to get us to help her around the house. But like Emily, I was determined to be myself, even if—maybe especially if—I had the same name as my mom.

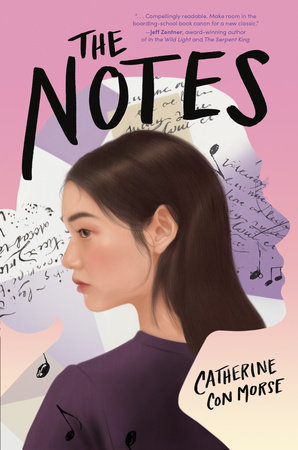

When Mom started writing, and publishing her work under our name, it pissed me off majorly. But it made sense, of course: She had always loved reading and writing. She had been an English major at Fu Jen Catholic University in Taipei. But publishing left and right while I was struggling to get published myself? Using my name? One Christmas, I had racked up some forty rejections from literary magazines, and meanwhile she boasted that she had been nominated for a PEN Award and gotten paid for a story. It felt like the last straw.

After Mom passed away, we were shocked to learn that in the course of three years, she had submitted to over four hundred lit mags and contests.

For a while, I didn’t even want to read Mom’s writing. It was painful to read about her feelings of being an outsider—in this country and even in her own family. She wrote about times she’d been hurt, and both the joys and struggles of being an immigrant, as well as a daughter, a wife, and a mother.

Because it was so unflinchingly honest and vivid, I’ll admit it: Mom’s writing was good.

In many ways, Mom was a model aspiring writer. She seized every opportunity offered, big or small. She wrote often, nearly every day. She read voraciously, but she also took her time, underlining words and jotting questions in the margins. She kept learning, and when it came to getting published, she kept trying. She wasn’t afraid to speak—or write—her mind, and she wasn’t afraid of hard emotions. That’s where good writing comes from, after all, and I can only hope that my readers and I can be as brave as her—even if she did “steal” my pen name.