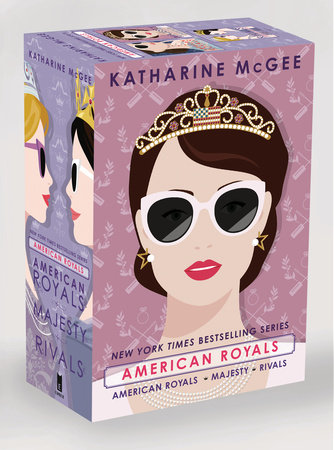

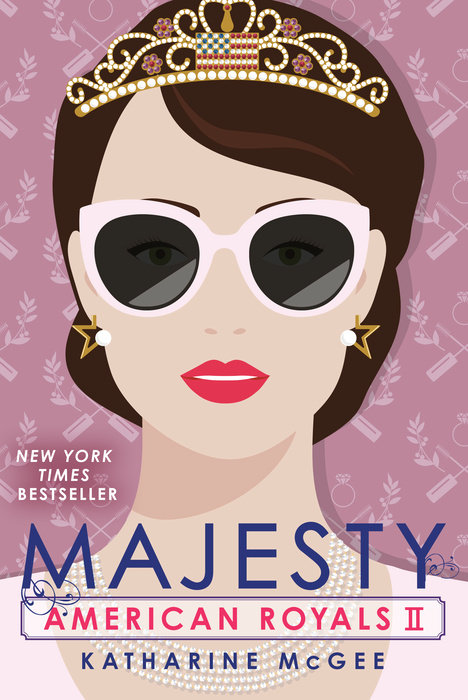

American Royals II: Majesty

America has its first ever queen on the throne in this sequel to American Royals! If you can't get enough of Harry and Meghan and Will and Kate, you'll love this New York Times bestseller that imagines America's own royal family--and all the drama and heartbreak that entails. Crazy Rich Asians meets The Crown. Perfect for fans of Red, White, and Royal Blue and The Royal We.

Power is intoxicating. Like first love, it can leave you breathless. Princess Beatrice was born with it. Princess Samantha was born with less. Some, like Nina Gonzalez, are pulled into it. And a few will claw their way in. Ahem, we're looking at you Daphne Deighton.

As America adjusts to the idea of a queen on the throne, Beatrice grapples with everything she lost when she gained the ultimate crown. Samantha is busy living up to her "party princess" persona...and maybe adding a party prince by her side. Nina is trying to avoid the palace--and Prince Jefferson--at all costs. And a dangerous secret threatens to undo all of Daphne's carefully laid "marry Prince Jefferson" plans.

A new reign has begun....