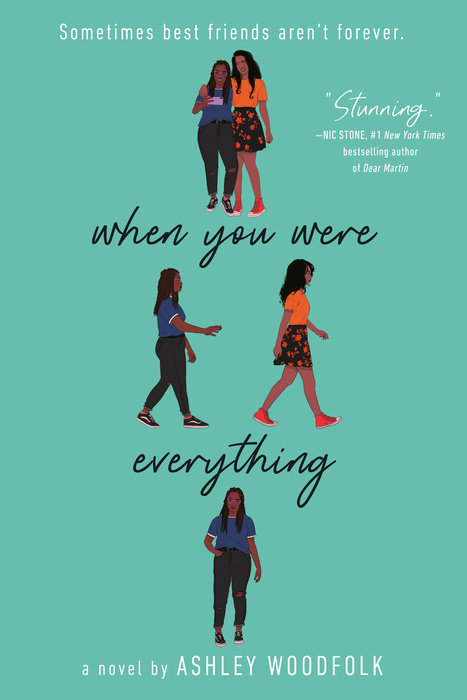

When You Were Everything

For fans of Nina LaCour's We Are Okay and Adam Silvera's History Is All You Left Me, this heartfelt and ultimately uplifting novel follows one sixteen-year-old girl's friend breakup through two concurrent timelines--ultimately proving that even endings can lead to new beginnings.

"Stunning." --Nic Stone, bestselling author of Dear Martin and Odd One Out

You can't rewrite the past, but you can always choose to start again.

It's been twenty-seven days since Cleo and Layla's friendship imploded.

Nearly a month since Cleo realized they'll never be besties again.

Now Cleo wants to erase every memory, good or bad, that tethers her to her ex-best friend. But pretending Layla doesn't exist isn't as easy as Cleo hoped, especially after she's assigned to be Layla's tutor. Despite budding friendships with other classmates--and a raging crush on a gorgeous boy named Dom--Cleo's turbulent past with Layla comes back to haunt them both.

Alternating between time lines of Then and Now, When You Were Everything blends past and present into an emotional story about the beauty of self-forgiveness, the promise of new beginnings, and the courage it takes to remain open to love.

"Breathtakingly beautiful....Woodfolk has a way of making words sing and burst with light." --Tiffany D. Jackson, award-winning author of Monday's Not Coming and Let Me Hear A Rhyme